Cyber Extortion

Data Held Hostage

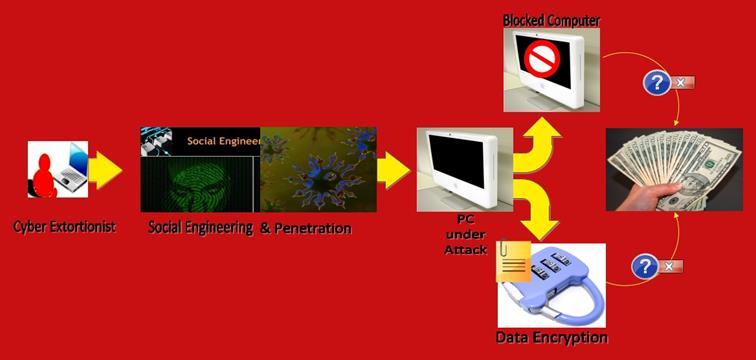

In the digital age, data has incredible value. Not only for business purposes, but also for criminal intent. It draws the interest of cyber extortionists, as legitimate users can be denied its value in many forms: by temporary encoding its substance (encryption), restricting data access (e.g., DDoS), and when the data is revealing and has a discreditable effect on the victim (e.g., extortion with digital video clips.)

Therefore, data can be seen as the new hostage. It can be held in a complex manner by replacing the encryption key existing in a database, and holding the new key hostage. Or, it can be held brute-force style via DDoS, or as simple as snatching the latest backup and deleting the original version from the owner's servers. This article will try to explain more about cyber extortion, the actors involved, and most probable repercussions.

Diagram 1

Tools & Targets

I. Tools

Ransomware

Ransomware, as the name suggests, is a type of malware specifically designed to block or encrypt data, followed by a ransom demand. A warning massage usually pops up explaining that an attempt to uninstall or inhibit the ransomware's functionality in any way would lead to an immediate deal-breaker. As mentioned before, an extortionist literally takes your data and system hostage.

Like most malware, ransomware spreads through social engineering techniques and traps sent from mostly unsolicited sources, such as spam, phishing emails with malicious attachments, links to bogus websites, and malvertising.

Once a victim's system is accessed, an encryption type of ransomware installs itself and launches a complete hard disc scan, in order to locate documents of interest. The next step is encryption, which converts the targeted files into an unreadable form. Non-encrypting ransomware programs typically 'lock' the entire PC, terminating all processes that are non-essential to paying the ransom, and can eventually receive an 'unlock' code.

Diagram 2

How Ransomware Functions

Finally, a ransom message is displayed on the victim's screen that demands a particular sum (usually between $100-1,500 for ordinary users) in exchange for a decryption key (usually claimed to be unique), thus completing a vicious cycle of cyber extortion crime done with the help of malware.

DDoS as a Means of Extortion

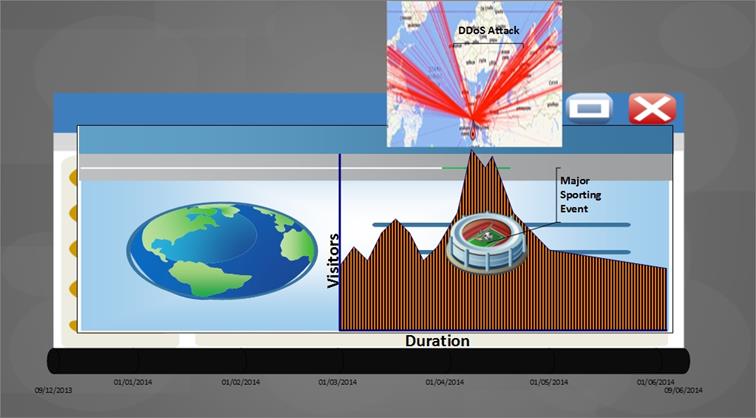

Another extortion tactic, and a very popular trend, is to threat a company's website or online business with a DDoS attack. Whether a DDoS is organized by extortionists, unfair competitors, or 'just for laughs' wanton troublemakers, is prima facie irrelevant. What is relevant is the realization that a DDoS imposed downtime might cost the targeted company a loss in revenue, clients, and prestige.

DDoS attacks have become an industry whose sheer power is at call for anyone willing to pay the price. And DDoS service prices are constantly going down, which also contributes to the epidemic proportions of this problem. According to Corero's survey, 38% of the respondents admitted that they had suffered one or more DDoS attacks in the past 12 months. Depending on how huge the target is, rates for downing websites vary from as little as $5 to $100 per hour. DDoS dealers circulate everywhere online, in underground forums, and even on the public internet.

Additionally, DDoS attacks are difficult to stop (see Layer 7 DDoS.) No one should be taken by surprise that massive DDoS attacks are a prefered weapon of choice, ready to submerge luxurious e-commerce websites during peak traffic times (Diagram 3.)

Similar to some instances of ransomware, DDoS attacks may be time limited in order to achieve a maximum psychological effect. Cyber extortionists justify the ransom size with crude calculations of the approximate financial negative impact on the victim's online business in the event of successful DDoS attack.

As an unwritten rule, most amounts of money asked for ransom demands are significantly lower than the potential financial loss on the victim's part. That's a purpose-built strategy intended as an incentive for the victim; temptation to redeem their peace of mind, pay the ransom like it's a minor nuisance, and move on.

At the end of the day, DDoS attacks can be monetized in many ways.

1. Targets

Most of the time, extortionists swing towards high-revenue generating online services, such as online gaming. Presumably, those would be more inclined to pay criminals to cease a DDoS incursion than owners of non-profit websites.

Online casinos are an appetizing meal for internet blackmailers because they're usually under-protected. To have to deal with criminal issues alone, larger gaming houses store more than $300 million on hand for the coverage of future debts.

The so-called 'digital shakedowns' on online gambling websites occur at their most profitable moments, such as the Super Bowl, NBA Finals and All-Star Game, NHL Playoffs and All-Star Game, FIFA World Cup, and Grand Slam tennis tournaments. During the course of those betting periods, cyber extortionists launch DDoS attacks that take a website offline. Then, they send a blackmail message to the owners, "typically demanding $40,000 to $60,000 in ransom in order to release the website so that users can return and keep playing."

Diagram3

DDoS Extortion Coincides with Major Sporting Events

Now malware can even take control of a webcam and record its owner. Hundreds of Australian visitors of adult websites were literally caught with their pants down and later blackmailed.

In Russia, malware planted child pornography, which cannot be deleted easily, and asked for a fee, otherwise a notification would be forwarded to the authorities.

A classic blackmail case on the internet is when users are recorded participating in cyber-sex sessions over webcam, and then threatened with footage. Evidently, most of the crimes in this group are performed by women, but men can also find a way to extort innocent women in such a manner. Could they be vengeful ex-employees? Yes, of course.

Cyber Extortion Could Take Down Companies

Money & Reputation

When being involved in extortion schemes, companies can suffer from breaches of sensitive information, serious reputation damage, loss of customers, and subsequent losses of income. In a way, we could imagine the resounding consequences of a successful cyber extortion on the victimized company reputation and assets by merely making a comparison with what happened with Apple's stocks when Steve Jobs' illness was announced or the Hewlett-Packard sexual harassment case, resulting in significant corporate turmoil.

Pulling Levers Can Be Easy

Cybercrooks have knowledge of the dynamics of consumer brand loyalty to particular online services. Simply put, if the customer is precluded from accessing their preferred website, sooner or later, they'll choose another provider, a surrogate, which has the same, or similar services available.

Selling Corporate Secrets

Unlike most perfunctory information, corporate secrets might possess considerable resale value to rival companies. The threat of resale can be a great motivation to pay blackmail ransoms.

Releasing Confidential Information

A particularly nasty method to perform cyber extortion is when extortionists threaten to release confidential customer information, such as names, credit card numbers and other credentials. Criminals' audacity goes as far as to publish confidential data on the victim's own website. The victim is at risk of being brought to court for exposing customers' private information, under the Insurance Portability Accounting Act of 1996 (HIPAA), and the Graham-Leach-Bliley regulations. Financial and healthcare companies can be held liable for such acts of disclosure. In addition, imposing hefty government fines are also possible.

Small Business

By definition, small businesses have the most to lose, given that they generally lack qualitative and sizable IT departments, and don't own a cushion of big profit and brand recognition. Therefore, they would rather sweep attempted or successful internet extortion attempts under the rug, with 'that is the cost of doing business' as a pretext. Consequently, therein lies part of the issue — the government and other empowered institutions cannot prosecute the wrongdoers without referrals, such as without being procedurally called upon.

Cyber Extortion Crimes Often Go Unreported

In spite of the growing number of cyber extortion cases, many injured parties, concerning all the ensuing negativity, are hesitant to get in touch with the authorities to apprehend criminals. The FBI reported that more than two-thirds of companies struck by a grievous cyber attack never report it. Nevertheless, based upon the great number of business now looking for protection and guidance, an impartial bystander can judge for themselves that this issue has a real presence and is gaining momentum.

Hence, the SANS Institute assesses that thousands of organizations are paying off cyber extortionists. Seemingly, they prefer to choose the lesser evil, at least from their point of view. Besides, a cybercrime fighter once confided that "after you pay the ransom, you don't generally advertise it."

And yet, there are signs that private companies already feel more comfortable discussing the problem of cyber security openly, because they're not the only entities to face these issues. Now that's a common occurrence.

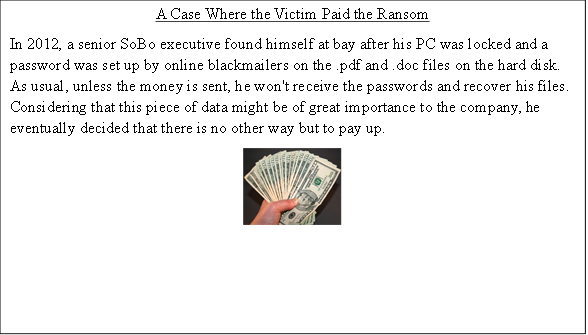

2. "To Pay, or Not to Pay": That is the Question

It's a dilemma that always reappears in the sufferers' minds. On one hand, "the first time it happens they are offended. They are upset. They look for help and can't get it from the law enforcement community, and so they make the payment." Then, on the other hand, a cornered person could say to themselves, "okay, so you paid them this time, but what's going to stop them from showing up tomorrow or the next day or the next week. Or even worse, you pay this time, but did they get any of your data and are they going to do anything with that?"

Paying the ransom may buy you some time, but that doesn't necessarily mean that you should feel secure. After all, the extortionists may not fulfil their part of the deal. Even if they do, they may give you a hard time later. A person in vulnerable position can never be sure that their vulnerability won't be exploited again and again. Moreover, there have been several cases where a decryption key was denied to victims because ethical hackers had managed to bring down the controlling servers.

How about breaking an encryption key? Most IT security experts noted that its length "would make it nearly impossible to obtain the key through computer brute force." They resigned to the belief that submitting to extortionists' terms is the only way to unlock what's encrypted. For reasons of defiance or impossibility to pay sudden expense, however, it has been estimated that only about 3% of targeted entities actually pay the blackmail ransom.

Conclusion

As the security firm Symantec warned for year 2013: "…attackers will use more professional ransom screens, up the emotional stakes to motivate their victims and use methods that make it harder to recover from and infection. In addition to targeting consumers, attackers will use ransomware to hold small business' data and system hostage." We can expect the same trend to progress even more in future, turning cyber extortion into one of the most popular cyber crimes for many more years to come.

Reference List

Boettger, L. (2013). Cyber Extortion – Why it's Never Good to Pay a Ransom. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://threepillarstechnology.com/cyber-extortion-why-its-never-good-to-pay-a-ransom/

Funaro, G. (2013). Ransomware & Cyber Extortion: Computers Under Siege. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://blog.kaspersky.com/ransomware-cyber-extortion/

Gow B. The Growing Threat of Cyber-Extortion. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://cf.rims.org/Magazine/PrintTemplate.cfm?AID=2713

Haley, K. (2012). Top 5 Security Predictions for 2013 from Symantec. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/top-5-security-predictions-2013-symantec

http://www.cbronline.com, (2013). Guest Blog: Cyber Extortion. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.cbronline.com/blogs/cbr-rolling-blog/guest-blog-cyber-extortion

Ibarra. R. (2013). Warning: The CryptoLocker Virus and Cyber-Extortion. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://geekscontrol.com/warning-the-cryptolocker-virus-and-cyber-extortion/

Narayan, V. (2013). In cyberextortion, pay ransom to unlock PC. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2013-11-10/internet/43885015_1_ransomware-malware-files

O'Connell, K. INTERNET LAW - Online Casinos Will Experience Cyber-Extortion During SuperBowl Betting. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.ibls.com/internet_law_news_portal_view.aspx?id=1967&s=latestnews

Peters, J. (2013). Cyber Financial Extortion: The big business problem no one wants to talk about. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.hacksurfer.com/articles/cyber-financial-extortion-the-big-business-problem-no-one-wants-to-talk-about

Schwartz, M. (2013). Cybercriminals Expand DDOS Extortion Demands. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.informationweek.com/security/vulnerabilities-and-threats/cybercriminals-expand-ddos-extortion-demands/d/d-id/1110534

Vaas, L. (2013). Polish programmers jailed for 5 years for DDoS and cyber-extortion of online casino. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2013/12/23/polish-programmers-jailed-for-5-years-for-ddos-and-cyber-extortion-of-online-casino/

FREE role-guided training plans

Wlasuk, A. (2012). Cyber-Extortion - Huge Profits, Low Risk. Retrieved on 07/01/2014 from http://www.securityweek.com/cyber-extortion-huge-profits-low-risk